|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Artist's Biography Exhibition Checklist Back to Evett Exhibition Past Exhibitions

Millenium, 1997 Maple with white stain, 93 1/2 x 62 x 16 1/2 in.(Photo: Ansen Seale)

Millenium, 1997 Maple with white stain, 93 1/2 x 62 x 16 1/2 in.(Photo: Ansen Seale)

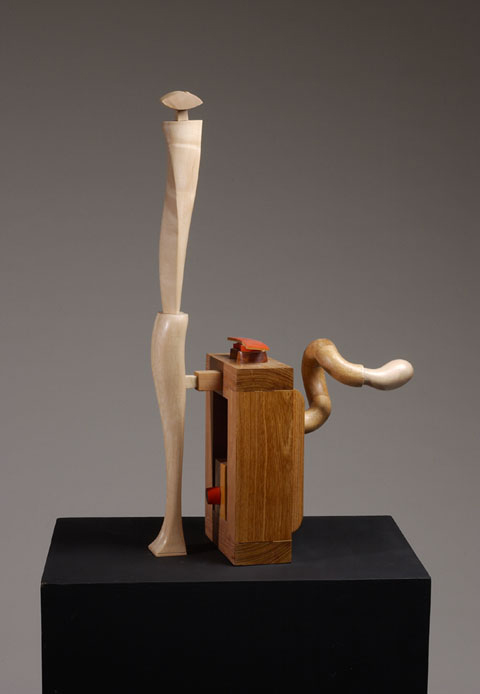

Saboteur, 2002

Maple, mahogany and paint 28 x 8 1/4 x 16 1/4 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

Saboteur, 2002

Maple, mahogany and paint 28 x 8 1/4 x 16 1/4 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

Santa Barbara, 2003 Cedar, mahogany and wenge base, 80 x 12 x 15 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

Santa Barbara, 2003 Cedar, mahogany and wenge base, 80 x 12 x 15 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

Hillwalker II, 2003 Mixed woods, 80 x 12 x 15 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

Hillwalker II, 2003 Mixed woods, 80 x 12 x 15 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

Fraulein, 2002 Cedar, cherry and mahogany, 75 x 20 x 18 in. (Photos: Ansen Seale)

Fraulein, 2002 Cedar, cherry and mahogany, 75 x 20 x 18 in. (Photos: Ansen Seale)

Stentorian (with detail), 2002 Maple, oak, cedar, mahogany and wenge, 104 x 14 x 14 in. (Photos: Ansen Seale)

Stentorian (with detail), 2002 Maple, oak, cedar, mahogany and wenge, 104 x 14 x 14 in. (Photos: Ansen Seale)

Gossip, 2003 Mahogany, maple and pecan, 50 x 17 x 10 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

Gossip, 2003 Mahogany, maple and pecan, 50 x 17 x 10 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

White Lila, 1990 Maple with paint and mahogany base, 37 3/4 x 6 1/2 x 10 1/2in.; base: 3 x 9 x 5 3/4 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

White Lila, 1990 Maple with paint and mahogany base, 37 3/4 x 6 1/2 x 10 1/2in.; base: 3 x 9 x 5 3/4 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)

(Left) Spirit of the 'Kendall Fish', 1995 Maple with cherry base, 32 x 22 x 6 1/4 in.

(Left) Spirit of the 'Kendall Fish', 1995 Maple with cherry base, 32 x 22 x 6 1/4 in.(Right) Spirit of the 'Kendall Fish, 1999 Cast bronze, 31 1/2 x 22 x 5 3/4 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale)  (Left) Diapason, 1987 Maple, 30 x 11 3/8 x 7 in.

(Left) Diapason, 1987 Maple, 30 x 11 3/8 x 7 in.(Right) Diapason, 1999 Cast bronze, 29 3/8 x 10 1/2 x 6 3/4 in. (Photo: Ansen Seale) |

Philip John Evett: The Aura of the Past/Future February 5–April 18, 2004 The Sculpture of Philip John Evett

In 1960, when I first saw an exhibit of some of Philip John Evett's early welded-steel pieces, I was so struck by them that I felt compelled to write a review of the show. It began something like this: 'There is among us a powerful force that we cannot ignore, nor, dare we be indifferent to it. That force is the artistry of Philip John Evett who has already distinguished himself as a contemporary master of figure sculpture.' If that was true more than 40 years ago, it is that much more true today.

Celebration of Lifeby Jim Valone In 1960, steel was very modern, stainless steel was more modern and welded steel was the most modern. Steel was - and is - the stuff we use to build big, tough, heavy-duty things, such as battleships, cannons, skyscrapers, suspension bridges, and automobiles. The significance of Evett's work, however, has absolutely nothing to do with modernity of the steel, but everything to do with what he made it do. Phil took large hunks of hard steel from automobile graveyards and turned them into remarkable organic forms of human anatomical parts. With his welding torch as chisel, he turned steel into fragile membranes, bones, organs and muscles that burst with living energy and all the vitality of human beings. What Phil did then - and is still doing today - was to create a new race of people who share our space or exist in our environment. These new creatures think, feel and do most things we do but without anger, prejudice or ill will. His is a clan of upbeat people who just don't happen to look much like you or me. Along with a new species of people, he invented a personal visual language to communicate a very profound and moving message. His vocabulary is abstract, but Phil's abstraction is the old, reliable kind - replace an 'old reality' with a new one that comes from the heart of the artist's imagination. For Phil, the 'old reality' is the human being and all the anatomical parts of the body - bones, muscles, organs and flesh. The true genius of Evett's work is his ability to replace all these organic parts with new forms that do not destroy the figure connotation of the statues. When I first viewed Evett's early welded-steel statues, I wondered if the figures were dissolving right before my eyes. Most of the statues were missing chunks of skin and outer flesh, making it possible to see the 'innards.' While I considered the idea of decay, an alternative also occurred to me. Perhaps it was the other way around - these figures were in their final stages of becoming, just completing some miraculous metamorphosis - LIFE: the celebration of life and the living of it. Ever since that moment, I have thought of all of Phil's work as his own perpetual celebration of life, probably because it simply isn't a bad notion at all. Each of his sculptures will always play a major role in that celebration, and they call to us all to join in with them. Two Conversations My friend Evett never has liked to talk about his own art. Naturally, I understand that. We do have to love the person who said, 'words were invented for people who can't draw.' Recently, in preparing to write this essay, I thought maybe Phil had mellowed a bit, so I called him to ask why some 90 percent of his statues are female. There was nothing but dead air between us. Then, eventually, with carefully chosen words he might use to explain to a child why the grass was green, he said, 'Well, (pause) I don't really know why (another long pause) but, it may have something to do with the fact that I've always thought that girls were prettier than boys (end of conversation).' No matter why, the female concept does pervade Evett's work, so much so that if his work is a celebration of life, it is also a celebration of the female spirit. Of course, 'Phil's Girls' go way beyond pretty. They are always elegant, self-assured and full of pride, representing the nature of womanhood. In another conversation with Phil, I asked him about his aluminum Crucifixion. Compared to the rest of Evett's work, this piece is quite different in many ways. First, it is not female, and then, it has nothing to do with the celebration of life. This is an image of Christ, suffering on the cross. I asked Phil why he chose this most recognizable symbol. This time, his answer was most evocative, dealing with history and, particularly, his history of World War II - nothing to do with the Christian faith. A lot of us, particularly those of us who had been in combat, felt some deep anguish and a sense of despair in the post-war years. We were living in a none-too-helpful age that had defined itself with the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Suddenly, this was a new age, the Atomic Age. How often does a society get to define itself in a matter of seconds? Phil chose the Crucifixion of Christ because he could use it as a symbolic requiem for all the death, torture, suffering and human degradation that had been thrust upon most everybody on our planet. Witness how PhilÕs Christ suffers for all mankind, this time for the sins of man's inhumanity to man. Impaled upon his cross, he writhes with pain and agony, looking toward heaven for answers that will never be given to the question, 'Why?' For me, this piece is among the most 'masterful' of Phil's many masterpieces. The Art of Space Like dance, architecture and theatre, sculpture is an art of space. The volumes and the space they occupy and/or enclose are real, i.e., not an illusion of three-dimensionality. Ergo, the size of a statue in relationship to the space it occupies is a most important design choice and is also directly related to the content of the work. For instance, big can mean imposing, sacred, impressive or many other things. And then there is little, which, like big, suggests a lot of other things, like portrait statues or other intimate things or images, even fetishes or charms. Between big and little is a vast space that can be filled by statues. The point is a simple one - in creating sculptured figures, the artist makes an important choice when determining size. There are two basic methods to create a statue. One is to carve away from a block of stone, marble or wood all the stuff you don't need. This is the 'subtractive' method. The second way is the 'additive' method in which things like clay are pressed into some armature and then more clay is layered upon other layers until the work is done. Phil's work, welding metals and building things from pieces of wood, is additive. In his artist's statement, Phil tells us that his process of adding things to stuff already in place is like a wonderful search. He continues to add this or that until the piece has the right shape and size for whatever concept got him started in the first place. This means that Phil determines the size of every piece simply by the length of time he needs to be satisfied that it is finished. So it is that there are Evett statues in this world that range from very small up to monumental ones, eight-, ten- or twelve-feet high. However Phil arrives at the size and length of his sculptures - intuition, magic or voodoo - it really does not matter because, in the end, the size of each piece is perfect. Poise, Contraposto or Precarious Balance? In the past 40-some years, Phil Evett's work has fallen into three different periods: the 'Age of Steel,' the 'Age of Aluminum' and the 'Age of Wood.' And now, a fourth, the 'Age of Wood and Aluminum,' may have started. Among and between his various ages, there are several differences, usually the result of the varieties in the materials themselves. And there are more than an equal number of similarities. Among these is the notable concern for balance that Phil has given every piece. Since a sculpture is three-dimensional and has its own height and size and takes up space in the world, balance becomes an integral part of this virtual-reality. That is to say, sculptors cannot ignore the center-of-gravity concept. No matter what, the statue must not tip over. Precarious balance is a fixed part of Evett's style, regardless of the material he uses. Indeed, it may be the most important part of his visual vocabulary because, after all, life is movement and vitality. This means that things can never be allowed to be static, dull or boring. They must be in action. Many of Phil's statues are single, standing figures in metal, clay, stone or wood, and all of them are doing something. They stand on one leg, twist or turn, gesture with their heads and arms. Each pose is a frozen moment in time. Also, notice how often these figures have long, thin and attenuated legs that support the bulk of weight above the halfway measure of the total figure! One might wonder, 'Are the ankles strong enough?' 'Will the legs break?' This is all part of this precarious balance between and among action, weight and the force of gravity that Phil composes so well. For examples of Phil's inventive treatment of single standing figures, look at some of his latest wooden pieces, like Bodecea, Twin Birth, or Cecil's Angels. As an added bonus, you will see that the vitality and drama of individuality are never compromised by repetition. The variety of size, shape and invented forms always identifies each figure as a singular entity. Phil's "Age of Aluminum" is, in my opinion, the most elegant of all. It is also the most decorative and complicated of all of Evett's work, as well as the most abstract or purely non-objective, full of complex and intricate surface treatment. But, it never gets far away from organic and visceral elasticity. Life is still the basic element; the sculptures have a heartbeat, a pulse that is visible. And there is something very sensual about the way molten aluminum bubbles and dries and what happens when it is polished or brushed. Phil also identifies his ladies with rounded breasts, buns-of-steel and lush contours of torso, arms and legs, but every gesture of every pose is always one that only a woman can make. Nowhere does Evett make this more evident than in the elegant women in his "Age of Aluminum. "New Age of Wood: Philip John Evett Today" Over time, Philip John Evett discovered some practical and obvious reasons to give up welding metal. With steel, there is the ever-present rust. With aluminum, it is the constant problem of oxidation that comes along with welding it. And, of course, metal is hard, cold and none-too-organic. But wood is warm and colorful, easy to shape. It's not always the same because of such beautiful variations as grain and density. Phil likely saw wood as the freedom to create a bunch of new shapes and volumes that cannot be made with welded metal. But whatever the reason, praise be to the goddess who made Evett do this! 'Elegance,' 'decorative,' 'complex surfaces' and near 'non-objectivity' may all be words to describe Phil"s metal sculptures. But, in this new age of wood, we need new words to define the joy of it. How about some of these words: delightful, lighthearted, whimsical, playful, funny and even profound and sexy? As it was more than 40 years ago, there is a powerful force among us that we cannot ignore, and we dare not be indifferent to it. That force is the artistry of Philip John Evett. Past Exhibitions | Current Exhibitions | Future Exhibitions | Back to Exhibitions |